Dependency Injection and IoC

This is also a way to achieve decoupling.

Core Concepts

DIP (Dependency Inversion Principle): High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions (interfaces or abstract classes). Abstractions should not depend on details; details should depend on abstractions.

IoC (Inversion of Control): Instead of a class creating its own dependencies via

new, those dependencies are provided externally — control is inverted.Dependency Injection (DI): A way to implement IoC — dependencies are injected into the consumer (via constructor injection, property/field injection, or method injection).

Why Use It (Advantages)

- Easier to test (can swap in mock or fake implementations)

- Reduces coupling, improves maintainability and scalability

- Clearer dependency boundaries and lifecycle management (especially with DI frameworks)

Common Implementation Approaches & Examples

1) Manual Dependency Injection (Simple, for small projects / testing)

Idea: Pass dependencies via constructor (constructor injection). It’s straightforward and great for unit testing.

// Interface and implementation

interface UserRepository {

fun getUser(id: String): User

}

class UserRepositoryImpl(private val api: UserApi) : UserRepository {

override fun getUser(id: String) = api.fetch(id)

}

// Consumer (ViewModel)

class UserViewModel(private val userRepository: UserRepository) : ViewModel() {

fun load(id: String) { /* use userRepository */ }

}

// Assemble dependencies manually

class MyApplication : Application() {

val userApi by lazy { UserApi() }

val userRepository by lazy { UserRepositoryImpl(userApi) }

}

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private lateinit var viewModel: UserViewModel

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

val repo = (application as MyApplication).userRepository

viewModel = UserViewModel(repo) // Injected here

}

}- Pros: Simple, explicit, easy to understand

- Cons: In complex object graphs or with scope management, it becomes verbose (too many

by lazy/ factories)

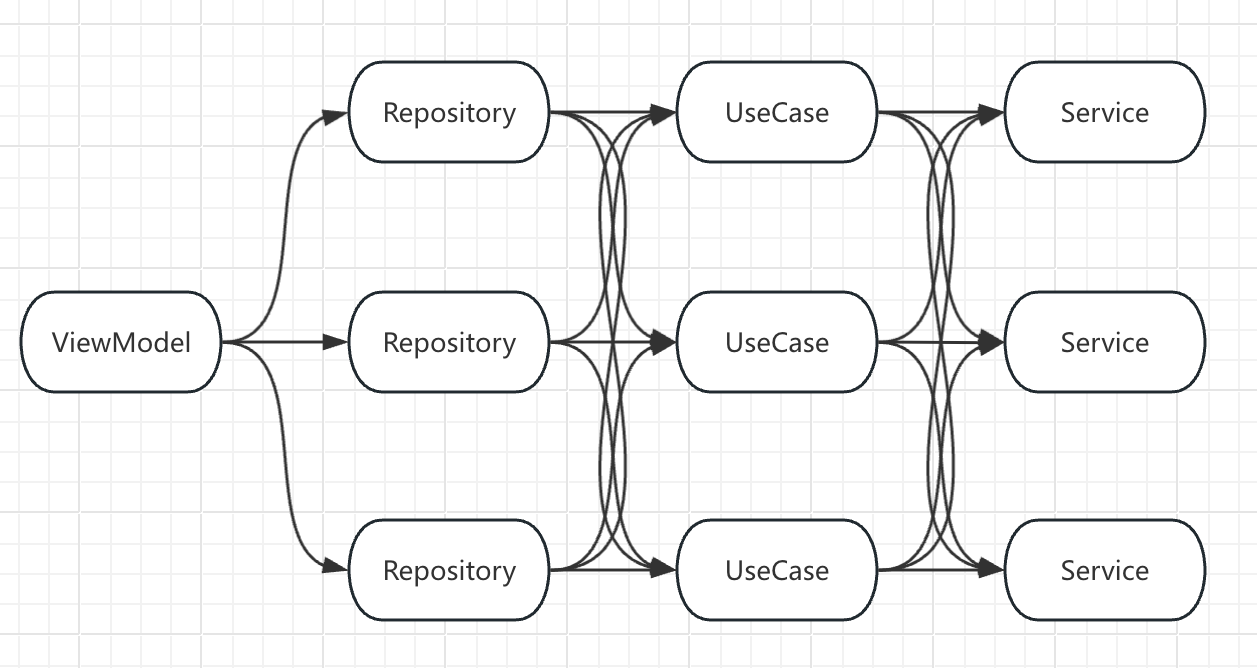

Google illustrates this with an analogy: When you create a car, you must provide its engine, tires, etc. But the engine itself may depend on other parts — how deep does the nesting go? In Android MVVM, the ViewModel might depend on a Repository, which depends on a UseCase, which depends on a Service:

class HomefeedViewModel(private val repo: HomefeedRepo)

class HomefeedRepo(private val useCase: HomefeedUseCase)

class HomefeedUseCase(private val service: HomefeedService)

class HomefeedService

class HomefeedViewModelFactory(

private val homefeedRepo: HomefeedRepo,

) : ViewModelProvider.Factory {

override fun <T : ViewModel> create(modelClass: Class<T>): T {

if (modelClass.isAssignableFrom(HomefeedViewModel::class.java)) {

@Suppress("UNCHECKED_CAST")

return HomefeedViewModel(homefeedRepo) as T

}

throw IllegalArgumentException("Unknown ViewModel class")

}

}Creating the ViewModel:

// Deeply nested "new" calls — complex and hard to maintain

val homefeedRepo = HomefeedRepo(HomefeedUseCase(HomefeedService()))

val factory = HomefeedViewModelFactory(homefeedRepo)

val viewModel = ViewModelProvider(this, factory)[HomefeedViewModel::class.java]2) Service Locator (Factory / Registry) — ⚠️ Controversial Pattern

Idea: Use a global registry to store and retrieve dependencies. Simplifies setup but hides dependencies (hurts testability and clarity).

object ServiceLocator {

private val singletons = mutableMapOf<Class<*>, Any>()

fun <T : Any> register(clazz: Class<T>, impl: T) { singletons[clazz] = impl }

@Suppress("UNCHECKED_CAST")

fun <T> get(clazz: Class<T>) = singletons[clazz] as T

}

// Initialization (Application)

class MyApp : Application() {

override fun onCreate() {

super.onCreate()

ServiceLocator.register(UserRepository::class.java, UserRepositoryImpl(UserApi()))

}

}

// Usage

class SomeClass {

private val repo: UserRepository = ServiceLocator.get(UserRepository::class.java)

}Note: Service Locator hides dependencies and introduces global state — generally not recommended.

3) Dagger / Hilt (Google Recommended for Medium–Large Projects)

Why: Compile-time injection, excellent performance, lifecycle-aware (Hilt). Most widely used in production Android apps.

Gradle (simplified):

implementation "com.google.dagger:hilt-android:2.x"

kapt "com.google.dagger:hilt-android-compiler:2.x"Example:

@HiltAndroidApp

class MyApplication : Application()

interface UserRepository { fun getUser(id: String): User }

class UserRepositoryImpl @Inject constructor(

private val api: UserApi

): UserRepository {

override fun getUser(id: String) = api.fetch(id)

}

@Module

@InstallIn(SingletonComponent::class)

object NetworkModule {

@Provides @Singleton

fun provideUserApi(): UserApi = UserApi()

@Provides @Singleton

fun provideUserRepository(api: UserApi): UserRepository =

UserRepositoryImpl(api)

}

@HiltViewModel

class UserViewModel @Inject constructor(

private val repo: UserRepository

) : ViewModel()

@AndroidEntryPoint

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private val vm: UserViewModel by viewModels()

}Key points:

@HiltAndroidApp: bootstraps Hilt@Module+@Providesor@Binds: provide dependencies@InstallIn: defines the scope (Singleton, Activity, ViewModel, etc.)- Constructor injection with

@Injectis preferred

4) Lightweight Container: Koin (Kotlin DSL, Runtime Injection)

Idea: Use Kotlin DSL to declare dependencies and load them at runtime. Simple and readable — great for small/medium projects.

val appModule = module {

single { UserApi() }

single<UserRepository> { UserRepositoryImpl(get()) }

viewModel { UserViewModel(get()) }

}

class MyApplication : Application() {

override fun onCreate() {

super.onCreate()

startKoin {

androidContext(this@MyApplication)

modules(appModule)

}

}

}

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private val vm: UserViewModel by viewModel()

}Pros: Simple, readable, quick to set up Cons: Runtime resolution overhead, less strict than Dagger/Hilt in large projects

How DIP Appears in Code

- Define dependencies via interfaces (

interface UserRepository) - Bind implementations to interfaces externally (e.g., module or factory)

- Inject via constructors (

class UserViewModel(private val repo: UserRepository))

→ High-level modules depend on abstractions, not concrete implementations.

Comparison of Injection Methods (Preferred Order)

- Constructor Injection ✅ — explicit, testable, and framework-friendly

- Property/Field Injection — acceptable in Activities/Fragments (used by Hilt)

- Method Injection — for special delayed injection cases

- Service Locator 🚫 — implicit, not test-friendly

Testing Strategies

- Provide fake/mock implementations for interfaces

- Replace modules in tests (Hilt:

@TestInstallIn; Koin: load test modules)

Practical Recommendations

| Project Type | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Small app / POC / learning | Manual DI or Koin |

| Medium–large / production | Hilt (or Dagger) |

| Performance critical / strict compile-time safety | Dagger or Hilt |

| Avoid | Manual new inside dependent classes (breaks DIP) |

Quick Checklist

- Do you use interfaces to abstract key dependencies? ✅

- Are dependencies exposed via constructor parameters? ✅

- Are scopes managed (Singleton, Activity, ViewModel)? ✅

- Are fake/test modules available for testing? ✅